Northern Ireland and the Defence of the United Kingdom

On the back of the news that Retired British Army Colonel Tim Collins OBE is to run for the Ulster Unionists as their North Down candidate in the next general election, and through the gift of Advisory Board Member Geoff Sloan, the Together UK Foundation is delighted to publish this magnificent article recently written by Col Collins.

In this article…

INTRODUCTION

When the south of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom in 1922 the geopolitics of the British state was recast. Despite granting Dominion Home Rule status to what was now known as the Irish Free State, British policy makers insisted on the maintenance of the geopolitical unity of the British Isles. This was to be done by the Royal Navy and the British Army retaining access to what was described as three ‘reserved ports’ located in Spike Island and protected by two forts covering the entrance to Cork Harbour, Berehaven in Bantry Bay and two forts located at the entrance of Lough Swilly.

The naval staff in October 1921 had made clear what was at stake in terms of a geostrategy: “Ireland, by reason of geographical position covering the most important sea approaches to the British Isles is a natural outpost of Great Britain’s inner line of defences. Ireland must therefore be brought to realise that the naval and strategic conditions in her case are of a special nature.” Paradoxically there was no mention of the role that the new devolved government in Northern Ireland was to play in Great Britain’s inner line of defences.

Northern Ireland had two unique attributes which were initially overlooked by Lloyd George and his civil servants. First, it was the most industrialised area of Ireland. Belfast’s GDP alone exceeded the whole of the Irish Free State. Secondly, it was to remain an important source of recruitment for the British Army and the armed forces. By 1922 six future Field Marshals with strong family ties to Ulster had just fought in and survived their first European conflict. It is also worth mentioning that in this conflict a total of 140,000 Irishmen both catholic and protestant had volunteered to fight. All Irishmen who survived and returned to the Irish Free State entered a very cold house.

THE INTER-WAR YEARS

The interwar era saw little defence activity in Northern Ireland. Indeed, the main contribution of Ireland as a whole during this period was the export of workers and soldiers to Great Britain to work in manufacturing and industry, and to police the Empire. A substantial part of the Royal Irish Constabulary, with 419 of their number killed – often murdered in lonely rural police stations – had left Ireland. Of those exiles, some 95% of the newly established 720 strong Palestinian ‘British Gendarmerie’, were ex-RIC. It was the men of the remaining Irish regiments, The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, The Royal Ulster rifles and the Royal Irish Fusiliers in the Line infantry, The 8th Kings Royal Irish Hussars and the 5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards of the cavalry and the Irish Guards, the youngest of the remaining Irish regiments, that made up the bulk of the young men heading overseas for adventure. And there was plenty of it with the line infantry seeing action in Waziristan in India, Shanghai and Palestine.

With the ascent to power in 1933 of the Nazi Party, the sinews of war that resided in the shipyards and aircraft factories of Belfast began to have greater traction. By the outbreak of the Second World War only one of the two shipyards in Belfast remained. The ‘wee yard’, Workman Clark, had closed in 1935, a victim of the depression. Harland and Wolff was, in contrast, stronger than ever. Diversifying into aircraft building amongst other products and it took a share in the newly created Shorts and Harland Ltd in 1936, building Bristol Bombay bombers and Hanley Page Hereford bombers under licence. The jewel in the crown of this period was the cruiser HMS Belfast, launched at H&W on St. Patrick’s day 1938. However, it was not only Queen’s Island that were stepping up production. Mackie International began retooling to make ammunition and the Sirocco Works stepped up its output, while Belfast’s rope making industry’s output grew to keep pace of not only the new Belfast built ships, but of an expanding Royal Navy. Elsewhere in the province small industries began to increase manufacturing capacity.

As the slide towards war continued, defence contracts placed with firms in Northern Ireland increased. Defence planners in London calculated the geographical distance of Northern Ireland from the nearest German airfields made it a safe haven for vital war industries. The key assumption in terms of geostrategy was the strength of the French Navy when combined with Royal Navy would be able to exercise sea control and sea denial in the Western Approaches. Consequently, few defence resources, air or naval, were allocated to Northern Ireland.

GEOSTRATEGIC HUBRIS AND WAR

Northern Ireland’s location in the British Isles, and a relative low density of population meant her initial experience of war would be much less austere than other regions of the United Kingdom. The threat of aerial bombing, rationing of food and other commodities and the general security measures (whilst sharing in adopting the blackout) all appeared less acute. This was compounded by the misplaced belief of the Stormont Prime Minister James Craig, as Northern Ireland was 550 miles from the nearest German airbase and given that any air attack would involve a journey of over 1,000 miles and necessitating crossing the heavily defended Great Britain twice, instilled, a false sense of security. As a consequence, Civil Defence measures were basic and air defences were practically non-existent.

Few defence planners in London or Belfast recognised the geopolitical implications of a British decision taken in 1938. The tectonic plates which sustained the geopolitical unity of the British Isles began to move. This strategic earthquake had its origins in the election of Eamon de Valera to the post of Irish Prime Minister in 1932. Almost immediately he broke unilaterally a number of provisions of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Oath of Allegiance to the King was abolished, the role of the Governor General was reduced, and the payment of Land Annuities was withheld. The United Kingdom responded by imposing tariffs on Irish agricultural imports.

By May 1936 the Chamberlain government had deluded itself into thinking a general settlement of this dispute would be facilitated by the UK giving up Articles 6 and 7 of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Agreement – the reserved ports. More dangerously the Chief of Staff of the Royal Navy, Admiral Chatfield, adopted a craven attitude by expressing a willingness to turn over these ports to the Irish government as long as they retained the right to use them in an emergency. De Valera made it clear that he would not give any such understanding. He even attempted to bring Northern Ireland’s constitutional future into these talks. In this respect he was rebuffed. Yet Malcolm MacDonald, Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs took this dysfunctional strategic thinking a step further in 1937 when he stated: “There was much more likelihood then, that if war came the Irish would come in on our side and much more likelihood of our being invited to use the ports in the common defence of our two countries”.

An agreement between the United Kingdom and the Irish government was signed on 25th April 1938. Giving up Britain’s rights to these ports constituted only a small part of the agreement. The majority of the clauses were concerned with financial and trade arrangements. The date for the final handover was set for 31 December 1938, just nine months before the beginning of the Second World War. When this agreement was debated in the House of Commons only one isolated backbench Tory MP correctly identified the extent to which the radius of action of RN ships would be curtailed (400 hundred miles without access to the bases at Queenstown and Berehaven). Even more importantly he correctly identified that this unforced geostrategic error, made possible the prospect of neutrality by the Irish Free State in any future war: “It seems to me that the danger which has to be considered, and which ought not to be excluded, is that Ireland might be neutral”. The name of the backbench MP was Winston Churchill.

NORTHERN IRELAND AS A GEOPOLITICAL PIVOT

At the beginning of 1939, with European war just eight months away, the Royal Navy found itself for the first time since the Williamite wars of 1689-97, without access to a naval base on the south coast of Ireland. It was 244 years since there had last been an absence of such basing facilities. This was compounded in May and June 1940 by the fall of Norway, the Low Countries and France. The geopolitical consequence of this meant that the German Navy now has direct access to the Western approaches. The ability of the Royal Navy to exercise sea control and sea denial in this area was now fatally compromised. This resulted in a momentous decision by the Admiralty in July 1940: this was to abandon the Western Approaches as a route for all convoys for the rest of the Second World War. In future all convoys would be routed ‘north about Ireland’. Consequently, Northern Ireland’s geopolitical importance had been accelerated. It was now the last remaining outpost of Britain’s inner line of defence. This rapid promotion brought with it a series of problems summarised by Captain Roskill RN the Royal Navy’s official historian of the Second World War: “The enforced use of the north-west approaches by all our shipping had, of course, not been foreseen or provided against, and in consequence properly equipped naval and air bases were lacking on the coastline bordering the focal waters”.

AN ARSENAL OF DEMOCRACY

It was in manufacturing industry and ship building that Northern Ireland was able to make a quick and decisive contribution to the war effort. Bombing raids on the Shorts works in Rochester, Kent, saw the main base of Shorts move to Belfast. As well as the obsolescent Herefords and Bombays built there, production of the home designed four-engine heavy bomber, the Short Stirling and the Short Sunderland flying boat, was increased. By the end of the war some 1,200 Stirlings and 125 Sunderlands would be built in Belfast.

Harland and Wolff build 140 warships and 123 merchant ships, repairing or converting more than 3,000 other vessels. Amongst the warships built were 6 aircraft carriers, Glory, Campania, Magnificent, Eagle, Warrior and Formidable as well as the cruiser HMS Black Prince, and HMS Penelope, a cruiser similar to HMS Belfast, which was made famous in CS Forester’s book ‘The Ship”.

Over 500 tanks (mainly the Churchill tanks, designed in Belfast and the mainstay tank of the British, Canadian and Australian forces) as well as Shermans (built under licence). 13 million other aircraft parts and 800-gun mountings were also produced. The linen factories produced some 200,000 yards of cloth for the forces as well as the fabric that covered the hurricane fighters and the gliders that would take the airborne forces to Normandy (including the 1st Battalion the Royal Ulster rifles [Airborne]) and air landed troops to Arnhem as well as 2 million parachutes. Factories in Londonderry produced some 30 million shirts for the armed forces. The Sirocco works constructed the ventilation equipment for the armament factories in Britain while James Mackie and Sons, along with other engineering plants produced 75 million shells and 180 million incendiary bullets. Belfast produced one third of all of the ropes used by the allied forces in this conflict.

In terms of agriculture, according to Queen’s University: ‘Northern Ireland also contributed significantly to the war effort. In 1941, it was the only region of the United Kingdom to reach its desired goal in the increase of acreage under the plough. During the same year, over 17,000 gallons of milk were being exported to Britain every day. The efforts of the Ministry of Agriculture to raise agricultural output, through Compulsory Tillage Orders and the introduction of a hire-purchase scheme for farm machinery, were highly publicised. Several unconventional locations – including strips of waste ground, golf course fairways and even the front lawn of Queen’s University Belfast – were turned over for the cultivation of crops in an effort to increase the amount of food being produced. Crops were also planted in the grounds of the Stormont Estate.’ By 1945, sustained efforts to increase the country’s food production had resulted in the total acreage of Northern Ireland’s agricultural sector roughly doubling relative to pre-war levels.

This manufacturing and produce capacity did not go unnoticed by the Third Reich. In late November 1940 Luftwaffe reconnaissance planes flew over Northern Ireland photographing the province’s installations. By early 1941 concerted bombing raids on population centres had brought horror to Britain and the devastation of Coventry had become a blueprint of terror in people’s minds. The complacency in Stormont had been replaced by a good intent, but all of the precautions envisaged were not adequate when the Luftwaffe attacked.

The ‘Belfast Blitz’ of April and March 1941 brought death and destruction. In four Luftwaffe attacks on Belfast, 1,100 people lost their lives, 56,000 houses – amounting to roughly half of the city’s total housing stock – were damaged and approximately 100,000 people were made temporarily homeless. During the first raid an estimated 754 people died. Luftwaffe pilots described Belfast as a ‘sea of fire.’ Only London suffered a heavier single night’s air raid. It was on this occasion that in desperation the Minister of Public Security, John MacDermott, phoned the Irish Government and requested that fire engines be sent North. Dublin sent fire volunteers and equipment from every available nearby town and city. De Valera for once took a pragmatic decision and briefly set aside ideology.

MANPOWER TO THE RESCUE

One of the more significant effects of these air raids was an uptick in volunteers for the armed forces. As well as citizens of Northern Ireland, many volunteers crossed the border from the Irish Free State to enlist. A 2013 study puts the numbers of Irish citizens who volunteered for war service as around 70,000. The reasons were many and complex. Many joined for adventure, some to fight Fascism & some out of loyalty to King and Empire. As Rudyard Kipling suggested in his poem ‘The Irish Guards’, there were also natural proclivities at play: “The Irish move to the sound of guns like salmon to the sea”. Moreover, about 4,500 soldiers of the Irish army deserted during the war and joined the British army. Investigating Irish officials regarded them as mercenaries, concluding that the higher rate of pay and family separation allowance attracted these men to the British army. On return they received harsh treatment and the families of those who fell in action were to experience even worse. The Irish Government put in place the so called ‘Starvation Order’ for all who served in the British Army. This historic wrong was only redressed by The Defence Forces (Second World War Amnesty and Immunity) Bill 2012, passed in the Dail in 2013, providing for the granting of an amnesty and immunity from prosecution to 5,000 Irish soldiers who fought with the Allies. They had been found guilty by a military tribunal of going AWOL.

As well as thousands of volunteers for the British Army, NI was to host another, much larger force. Shortly after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour, bringing the USA into the war, the UK and US established the Combined Chiefs of staff for the coordination of the allied war effort. The main coordinator on the UK side was Field Marshal Sir John Dill and on the US side, General George Marshall. President Roosevelt described Dill as “the most important figure in the remarkable accord which has been developed in the combined operations of our two countries”. It was Sir John Dill who, exerting his significant influence over the US, established the ‘Germany First Policy’. The result of that was that the US Army, in 1939 with a strength smaller than Portugal’s army, had to be rapidly expanded. Then it had to get to the fight. The entry point for the US Army into the European theatre was Northern Ireland. Some 300,000 US troops would eventually pass through Northern Ireland at one time representing 10% of the population. Of particular significance, the US Army decided that it needed a force similar to the UK Commandos. On 19th June 1942 the US Rangers were founded in Boneybefore, Carrickfergus, Co Antrim. Additionally, the US recognised the utility of airborne forces and so the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions were created. By 1942 12,000 men of the 82nd Airborne would be stationed across the province. In a speech at the City Hall Belfast in August 1945, General Dwight D Eisenhower said “Without Northern Ireland, I do not see how the American forces could have been concentrated to begin the invasion. The city of Belfast, its facilities, people, and influences made possible the beginning of that concentration”. This was not Eisenhower’s fist and only visit to the province. In 1944 he and General Montgomery met at Knockamoe Castle near Omagh in Co Tyrone as part of secret planning for D Day, around one week before the actual landings.

Soldiers from Northern Ireland had been serving since the beginning of the war. It is estimated that in excess of 38,000 volunteered for war service including 7,000 women. The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers found themselves in the brunt of the unsuccessful Arakan campaign of 1943 suffering significant casualties, whilst the Inniskilling Dragoons, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, Royal Ulster Rifles and the Royal Irish Fusiliers were all evacuated from Dunkirk. The Irish Guards held the rear guard at Boulogne before evacuation. They also saw action in the ill-fated Norway expedition. Irish soldiers would go on to fight in every theatre from North Africa to Burma and from Sicily to Italy, with both battalions of the Royal Ulster Rifles landing on D Day – The 1st battalion by air and the 2nd battalion by sea. Individual Ulster men would distinguish themselves elsewhere in the war. A number of Ulster Riflemen joined the Army Commandos and Captain, (later Major General) Corrin Purdon won a Military Cross (MC) during Operation Chariot, the raid on St Nazaire. He would later escape from Colditz castle before being re-captured. Two of the founding members of the SAS, Robert Blair Mayne and Eoin McGonigle were also Ulster Riflemen (Mayne would go on to be the legendary commander of the SAS – McGonigle was killed in North Africa) as were many individual SAS men including Trooper ‘Tot’ Barker as well as Troopers, Vary, Walker and Young. Sadly all of these men were murdered by the SS, having been captured after betrayal by the French Resistance as part of the Dublin born Captain, ‘Paddy,’ Garstin ‘Stick’. The Garstin ‘Stick” was all Northern Irish except for Lance Corporal Vaculik, who was a Sudeten German serving with free French (and who escaped). Corporal Lutton from Co Armagh, also part of the Stick, had died of wounds in captivity shortly before. Scores of Ulster men and Irish men would serve elsewhere in the SAS including Mayne’s driver Corporal Billy Hull from Belfast.

The exploits of the Royal Ulster Rifles, The Irish Guards, the Inniskilling Dragoons and the Irish Hussars in Northern Europe and the Irish Fusiliers and Inniskillings in Italy are well documented. From the slopes of Monte Cassino to the Irish Guard’s role in Operation Market Garden – The Battle of Arnhem – onto the exploits of the Ulster Rifles Airborne participation in the Rhine crossings, Northern Ireland was represented in every theatre. In the Far East Northern Irishmen were marching with the Chindit columns, fighting with Royal Inniskillings Fusilier’s second Battalion and with one of the Royal Artillery Regiments raised in Belfast. In the air and on the waves, Northern Irishmen and women, fought in the RN, RAF and merchant navy often at terrible cost.

THE GEOSTRATEGY OF BASING

As Captain Roskill RN had correctly identified the non-existent basing structure was a real challenge for the Royal Navy. What was hidden at the time was that Northern Ireland had become a focus of US military planning for naval bases. The US navy secretly approved plans in March 1941, nine months before the attack on Pearl Harbour, to build two bases, one in Londonderry and the other in Lough Erne. Construction began in June 1941. HMS Ferret, the Londonderry shore base, was operational from the summer of 1940 to facilitate repair and refuelling of naval escorts. By 1943, the number of escorts there exceeded the combined totals of Liverpool, the Clyde and Belfast.

At the height of the Battle of the Atlantic 139 naval escorts had their home base either in the city, or at Lisahally, where the Admiralty had built a new jetty. Some of the most famous U-boat hunters of the war were based at Londonderry. Donald Macintyre, “Johnnie” Walker, Peter Gretton and West Cork man Evelyn Chavasse. He commanded escort groups operating from the city.Along the shores of Lough Foyle, the Royal Air Force added its contribution, with airfields at Limavady, Ballykelly, Eglinton and Maydown. Both Eglinton and Maydown were handed over to the Admiralty in May 1943, as was the Army’s Ebrington Barracks.RAF Ballykelly became one of Coastal Command’s most important stations. The naval air stations at Eglinton and Maydown assumed considerable significance. Eglinton – now City of Derry Airport – was an important training station, while Maydown, became home to Swordfish biplane bombers that flew off converted merchant ships (MAC-ships) supporting convoys from mid-1943 onwards.’ If you pause on your way into the terminal at The George Best City Airport in Belfast you will see a memorial to the pilots of the catapult launched Hawker Hurricane fighters of Catapult Armed Merchantmen (CAM). The aircraft, once launched, would take on enemy aircraft before ditching in the sea, where the pilot would (hopefully) be recovered. During the war there were eight launches, eight enemy aircraft accounted for the loss of a single pilot.

The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest campaign of the Second World War. The first sinking by a U boat being on the very day Britain entered the war, and the last on the day of surrender itself. Londonderry had been transformed. For example, the US spent $75 million on installations, and the population soared as Naval personnel and dockyard workers were posted in and recruited. The US base Springtown comprised of 302 huts, a chapel, laundry, dining facility, barber shop, theatre and its very own jail.

In this campaign 2,500 merchant ships were sunk in the Atlantic. This was equivalent to 11.5 million tons. The Merchant Navy lost over 30,000 men. Almost half the 341 Royal Navy warships lost during the war went down in the Atlantic, along with a large proportion of the more than 51,500 sailors who perished. The U-boat fleet lost almost 700 boats and more than 32,000 men killed, with 5,000 captured. Their death toll was frightening – some 82% of personnel; total U- boats lost represented almost 84% of those built and commissioned. No other combatant arm of any nation in the Second World War suffered such a high death rate. More than 100,000 individuals lost their lives in the Battle of the Atlantic. When Hitler’s successor as Fuhrer, Grand Admiral Karl Donitz, ordered the U-boats to surrender on May 4, he also told their crews that, “undefeated and spotless, you lay down your arms after a heroic battle without equal”.

VICTORY AND ITS SHADOW

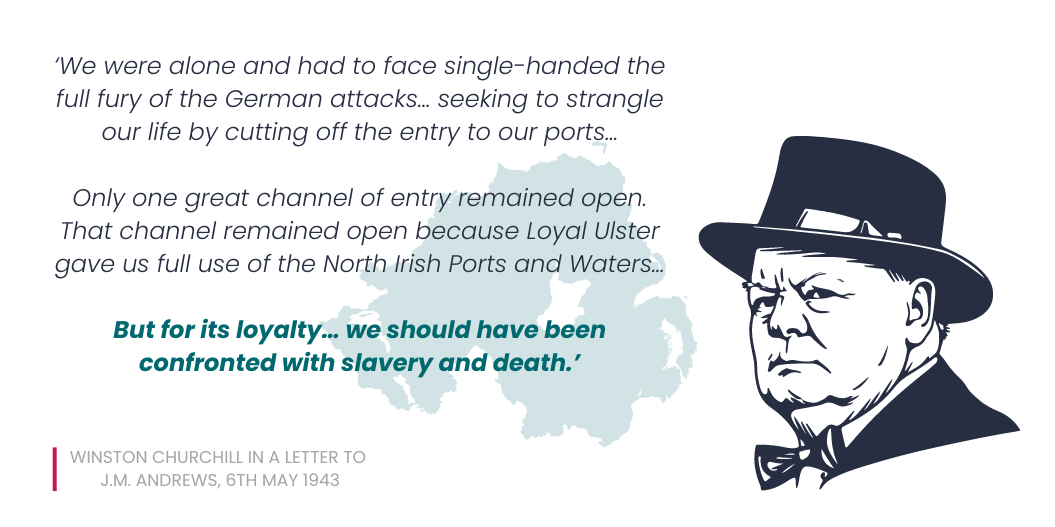

By 1945 the geopolitical unity of the British Isles had been recast for the second time in 23 years. Northern Ireland had exceeded all the expectations placed on it. Winston Churchill declared in his victory speech of 13th May 1945 that but for Northern Ireland’s “loyalty and friendship” the British people “should have been confronted with slavery or death,”. The words were apt indeed. A day after he spoke, on 14th May 1945, what he later described as his “greatest fear”, one hundred and sixteen of the one hundred and fifty-seven surviving German U boats were gathered at Lisahally in County Londonderry for surrender. The very reason the surrender was taking place in Northern Ireland was that it was from Lough Foyle that the allied ships had defeated the U boats. Working closely with bases in Scotland, Liverpool and Larne and supported by the RAF, RCAF and USAAF aircraft from bases in Northern Ireland and flying over the ‘Donegal corridor” the spear tip of resistance against the U boat menace was Londonderry. It was from here that the radius of action and speed of advance, two pivotal aspects of the geography of naval warfare, could be maximised.

The shadow over this victory was Irish neutrality. This was made possible by the appeasement of the Chamberlain government in 1938. It also provided opportunities for that extreme element of Irish Republicanism, the IRA. Sean Russell was Chief of Staff of the IRA in 1940. He died onboard U-65 off the coast of Galway on route back to Ireland from Germany whilst travelling with IRA man Frank Ryan and was buried at sea. (Ryan would later die in Berlin towards the end of the war). A controversial figure, Russell’s statue in Dublin was decapitated in December 2004. A justification issued to the press by the unknown group said ‘Russell was one of many nationalist fanatics who looked to Hitler for political and military support in the IRA’s quest to reunify Ireland at the point of the bayonets of the Gestapo.’ At the Wanasse Conference, the infamous Nazi gathering that planned the “Final Solution”, the Jewish community in Ireland was marked down for annihilation. Having freed Ireland from British rule, the Nazis expected their collaborators to help them round up Dublin’s Jews and ship them off to Auschwitz. That was the price Sean Russell was prepared to pay for an enforced united Ireland. The Guardian identified the actual bargain the IRA struck for the support of the Nazis in a report dated 7th Sept 2003. This was a list of 3,700 Jewish men women and children designated for extermination.

FIGHTING THE COLD WAR

The political shock of this immediate post -war period was the declaration on 7th September 1948 that the south of Ireland would become a republic and leave the commonwealth. A secret report of the Cabinet Office in January 1949 recognised a new strategic imperative that consolidated the wartime recast of the geopolitical unity of the British Isles; “it will never be to Great Britain’s advantage that Northern Ireland should form part of a territory outside His Majesty’s jurisdiction. Indeed, it seems unlikely that Great Britain would ever agree to this even if the people of Northern Ireland desired it”.

In the Province itself the task at hand was rebuilding and modernising. Large numbers of pre-fabricated homes, ‘Pre fabs’ as they were known, sprung up across Belfast. Some of them would survive into the 1990s. Work for the shipyard continued with the focus moving to tankers and away from the traditional cruise liner work. The Royal Navy had several vessels built in Belfast including the two Hermes class aircraft carries ‘Bulwark’ and ‘Centaur,’ which would serve throughout the turbulent period of withdrawal from Empire and the Cold War.

It was in one of the proxy wars of the Cold War that Northern Irishmen were to make a vital contribution. In 1950, the Russian backed regime of Kim Il Sung made a desperate gamble to re unite the Korean peninsula by invading the South. With the South Korean Army and a small US garrison on the verge of collapse, a US backed UN force counterattacked driving the North Koreans to the very borders of China. Fearing for her own security, China counterattacked driving the UN forces south again. By April 1951 the frontline had stabilised roughly at the pre-war border.

The UN force now included a number of national contingents including a UK Brigade and Commonwealth Brigade which was part of the order of battle. The UK 29th Brigade included infantry from the 1st Battalion the Royal Ulster Rifles and the latest Centurion tanks of the 8th Royal Irish Hussars. In December 1950, in conditions of extreme cold, the Northern Irishmen were moved forward to defend the 38th parallel from an expected Chinese attack. That attack would come on 1st January 1951. The steadfastness and courage of these soldiers would stop the initial Chinese attack in front of their positions – but at a cost. In this, their first major action of the war, during 3/4 January 1951, the Battle of Chaegunghyon (Happy Valley), the Rifles did not lose an inch of ground and successfully covered the withdrawal of the UN forces to the South of the Han River. Eventually when the time came to withdraw from their positions the Chinese were already behind them and the Rifles had to fight their way out. Those Ulster Riflemen captured during and immediately after the battle suffered exceptionally, not only from the severe winter weather, but also from a lack of organisation by the Chinese regarding their evacuation. There are no published accounts by survivors of this column, but one, believed to be Corporal William Massey, kept a diary of his experiences while a prisoner and he managed to smuggle this out of the camp when he was repatriated. Massey wrote on both sides of a single sheet of rice paper using minute writing and was able to record the names of many of the eighty-three other ranks and five officers taken with him, along with details of the hardships they endured. The Battalion had lost 157 men, killed captured or missing. There was real concern at home. This was addressed by the War office on 12th January in the Northern Irish press:

‘In view of reports that the Royal Ulster Rifles had been wiped out in recent actions in Korea, the War Office states that official reports do not in any way indicate that this is so and in fact, state that all units of the 29th Brigade are still in action and in very good heart, though the Brigade has sustained casualties. Next of kin are being informed as and when casualties are notified to the War Office.’

Reinforced back to full strength, the Ulster Rifles once more moved into the line along with the Irish Hussars in April where it was part of the US 1st Corps. Unknown to them, it faced the Chinese 19th Army Group comprising the 63rd, 64Th and 65th Armies – each comprising 3 Corps and the 8th Chinese Artillery division. With a numerical superiority of eight to one, it was the intention to wipe out the UN forces and re capture the South Korean capital Seoul.

The Battle of Imagine which followed, has become associated with the last stand of the Gloucestershire Regiment, which was effectively wiped out. But at both the junior and senior divisions of the British Staff College, it is the self- extraction of the Royal Ulster Rifles and the 8th Royal Irish Hussars that is taught as a text-book withdrawal in contact. A first-hand account stated: ‘By now skirmishes were erupting along the track between the retreating infantry and squads of infiltrators. ‘We were fighting our way out,’ said Corporal Farrell (a former light welter weight boxer from Belfast). ‘They came running at us; we had a wee bit of a dig at them.’ Still, there was no panic. ‘I don’t remember being sort of frightened that way – we were quite capable of taking them on. Every time we’d met ’em, we’d hammered ’em.’ Fighting, often hand to hand and outnumbered in places at up to ten to one, the Centurion tanks of the Hussars took to machine-gunning each other and even firing canister shot at each other’s tanks to clear off the Chinese masses climbing onto them.

In his book, A New Battlefield, David Orr describes what came next: ‘An hour later the battle was over, with the last of 29 Brigade including the two Centurions safely behind the Main Supply Route. Major Huth, C Squadron commander, in his tank ‘Cameronian’, was the last to leave the battlefield. One of his tank commanders, Richard Napier, recalled, “after about three hours of continuous firing, my machine-gun barrels needed changing; my recoil system was so hot it wouldn’t run back and my loader/operator Ken Hall, had fainted with the continual hard work and fumes.” The Centurions were a macabre sight, their turrets and hulls smeared with blood, their tracks dripping with intestines, skin and pieces of ragged uniforms, both Chinese and British. It was the general opinion among the survivors of the Brigade that Major Henry Huth should have received the Victoria Cross for his actions. In the Rifles, Major Rickcord, acting Commanding Officer, stated that Huth was an absolute professional and master of his job “The man of the match and if one more VC was deserved for this action it should have gone to Huth!” As for the Rifles, Gerald Rickcord noted that not an inch of ground had been ceded on the Imjin, prior to the order to withdraw. The men of 29 Brigade rallied, formed into a column and with the two tanks once again defending the rear began the march south towards Uijongbu. After a four-mile march the Brigade reached the crossroads at Tokchon. A much-relieved Brigadier Brodie visited Major Rickcord and expressed surprise that B Company, who had acted as rear-guard, had made it. He then informed Rickcord that the Battalion must expect to fight another battle and they must begin to dig in at once. Rickcord recalled that it was odd to hear the clink of picks and shovels going again. When the roll call was made in the Rifles, it showed a total strength of fourteen officers and 240 other ranks.’ But the road to Seoul was saved and thanks to the efforts of, amongst others, the Royal Ulster Rifles and the Irish Hussars, the UN front line did not collapse, and South Korea was spared once more.

POST-WAR TECHNOLOGY AND SHIPBUILDING

Back home in Belfast the advent of the jet-powered airliner in the late 1950s, meant the demand for ocean liners declined. This, coupled with competition from Japan, led to difficulties for the British shipbuilding industry. Harland and Wolff launched the MV Arlanza, for Royal Mail Line in 1960, whilst the last liner completed was SS Canberra for P&O in 1961.

In the 1960s, notable achievements for the yard included the tanker Myrina, which was the first super-tanker built in the UK and the largest vessel ever launched down a slipway in September 1967. In the same period the yard also built the semi-submersible drilling rig Sea Quest which, due to its three-legged design, was launched down three parallel slipways. This was a first and only time this was ever done.

In the mid-1960s, the Geddes Committee recommended that the Government advance loans and subsidies to British shipyards to modernise production methods and shipyard infrastructure to preserve jobs. A major modernisation programme at the shipyard was undertaken, centred on the creation of a large construction graving dock serviced by two Krupp Goliath cranes, the iconic Samson and Goliath, enabling the shipyard to build much larger post-war merchant ships, including one of 333,000 tonnes. Amongst Royal Navy Ships completed was HMS Fearless which was to see action in the Falklands war in 1982.

Continuing financial problems led to the company’s nationalisation. The nationalised company was sold by the British government in 1989 to a management/employee buy-out in partnership with the Norwegian shipping magnate Fred Olsen; By this time, the number of people employed by the company had fallen to around 3,000.

For the next few years, Harland & Wolff specialised in building standard Suezmax oil tankers and has continued to concentrate on vessels for the offshore oil and gas industry. It has made some forays outside this market, Harland & Wolff’s last shipbuilding project was MV Anvil Point,[13] one of six near identical Pointclass Sealift ships for use by the Ministry of Defence. The ship, built under licence from German shipbuilders, was launched in 2003.

AIRCRAFT TECHNOLOGIES

Across the way at Shorts, taking full advantage of a close cooperation with Queen’s University Belfast’s Engineering Faculty, aircraft and missile innovation and production thrived. By 1947, all of Shorts other wartime factories had been closed, and operations concentrated in Belfast. In 1948, the company offices followed and Shorts became a Belfast company in its entirety. In the meantime, in 1947, Short Brothers (Rochester and Bedford) Ltd. had merged with Short and Harland Limited to become Short Brothers and Harland Limited.

In the 1950s, Shorts was involved in much pioneering research, including designing and building the Vertical Take-off or Landing (VTOL) Short SC1, the Short SB5 and the Short SB4 Sherpa. Shorts built the Short Sperrin, a backup jet engine bomber design in case the Strategic nuclear V Bomber projects failed, and the Short Seamew, a cheap to produce anti-submarine reconnaissance and attack aircraft intended for the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) squadrons, but the Sperrin was not needed and the RNVR squadrons disbanded. In the 1950s, Shorts also received sub-contracts to build 150 English Electric Canberras, and on 30 October 1952, the first of those made its maiden flight. Of these types, Shorts delivered 60 Canberra B.2s, 49 Canberra B.6s and 23 Canberra P.R.9s, the remaining 18 being cancelled by the Government in 1957. Further work was involved in the conversion of time-expired Canberra B.2s into unmanned radio-controlled missile target aircraft. Two prototypes and 10 production Canberra U.10s were produced, followed by six improved Canberra U.14s. These aircraft were controlled from the ground by VHF radio and were equipped to provide feedback on their own performance, as well as that of the missiles aimed at them. As early as 1953, Shorts became involved with pioneering the development of electronic analogue computers, to assist with the design of increasingly complex aircraft.

In 1954, the Bristol Aeroplane Company became a 15.25% shareholder in Shorts, and the company used the injection of funds to set up a production line for the Bristol Britannia airliner, known in the press as The Whispering Giant. Although it was originally intended that 35 Britannias should be built by Shorts, a shortage of work at Bristol led to this number being reduced. Eventually, 15 Britannias were completed by Shorts; five sets of Britannia components were sent to Filton and used on the continued production there of Britannias.

In the 1960s, Shorts found a niche for a new short-haul freighter aircraft and responded with the Short SC7 Skyvan. The Skyvan – still in service today with contractors supporting the UK MoD to deliver the UK’s parachute training capability, is most remembered for its box-like, slab-sided appearance and rectangular twin tail units. But the aircraft was well loved for its performance and loading. It served almost the same performance niche as the famous de Haviland Twin Otter, and the Skyvan proved more popular in the freighter market due to the large rear cargo door that allowed it to handle bulky loads with ease. Other Skyvans can still be found around the world today, notably in the Canadian Arctic.

The heavy lift freighter Short SC5 Belfast flew for the first time in 1964. Only 10 were built for the RAF. In the 1970s, Shorts entered the feeder liner market with the Shorts 330, a stretched modification of the Skyvan, (called the C-23 Sherpa in USAF service), and another stretch resulted in the more streamlined Shorts 360, in which a more conventional central fin superseded the older H-profiled twin fins.

In 1988, the proposed development was announced of a Regional Jet seating 44 passengers and to be called the FJX. The aircraft would have been a competitor to the Bombardier CRJ100 that was also in development at the time, but the FJX was cancelled after Short Brothers’ sale to Bombardier.

MISSILE TECHNOLOGY

It was the late 1950s that the UK Ministry of Defence instructed Shorts to develop a missile design and production capability as missiles increasingly replace guns and artillery in air defence and naval warfare. Now, amongst the first missile factories in the world, Shorts got to work on several systems. One of the most famous in naval circles was the ‘Seacat’. Seacat was a British short-range surface to air missile system intended to replace the ubiquitous Bofors 40mm gun aboard warships of all sizes. It was the world’s first operational shipboard point – defence missile system and was designed so that the Bofors guns could be replaced with minimum modification to the recipient vessel and (originally) using existing fire-control systems. A mobile land-based version of the system was known as Tigercat. Seacat and Tigercat would go on to be the antiaircraft weapons system for 23 nations. Designed in 1962, it is still in service in some countries today. Other Belfast origin missile systems include a family of missiles developed for the Army. Shorts ‘Blowpipe’ is a man portable (MANPADS) surface to air missile that was in use with the Armed Forces from 1975. It also saw service in other military forces around the world. Most examples were retired by the mid-1990s. It is unique among MANPADS in that it is manually guided to its target with a small joystick, sending guidance corrections to the missile over a radio-controlled link.

Blowpipe underwent a protracted and controversial development between the program’s initial conception in 1966 and 1975, when it finally entered service. It had its first use during active combat in the 1982 Falklands war when it was used by both sides of the conflict. The Javelin replaced the Blowpipe and was itself superseded by Starburst. The system that came next and is still in service today, it is also known as Starstreak HVM (High Velocity Missile). After launch, the missile accelerates to more than Mach 4, making it the fastest short-range surface-to-air missile in the world. It then launches three laser beam riding submunitions, increasing the likelihood of a successful hit on the target. Starstreak has been in service with the UK Armed Forces since 1997. The Belfast Thales plant continues to be a cutting-edge technology with several 21st century systems ether in test phase of entering production with components produced at several sites across the province. Today the Swedish designed but Belfast produced NLAW (Next Generation Light Anti-Tank Weapon) is one of the wonder weapons that allowed Ukraine to defend itself from the Russian Invasion of 2022. It is in service alongside the Belfast designed and made Starstreak missile system, both weapons systems being produced around the clock since the outbreak of the conflict.

DEFENCE CLOTHING

Elsewhere, other defence companies are important to the UK’s defence. Cooneen Defence are a military clothing manufacturer that meets the clothing needs of police and military across the globe. For 15 years now, Cooneen have been producing military clothing of every type including combat clothing to parade wear. When you see the gear the UK military – and indeed the military of several nations, are wearing in the field, remember that was made in Northern Ireland.

CYBER SECURITY

Cyber security is one of Northern Ireland’s fastest growing technology sectors, with several home grown companies working alongside several US companies who have chosen NI as their destination of choice. Such is the demand that there is a skills shortage of talented cyber specialists in the virtual petrie dish of this vital technology. Once again it is Queen’s University Belfast that has been leading the way with The Institute of Electronics, Communications and Information Technology. The institute is host to the award-winning UK Innovation & Knowledge Centre for cyber security, The Centre for Secure Information Technologies, ECIT also houses The Centre for Wireless Innovation and The Centre for Data Science and Scalable Computing.

The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) has been collaborating with its Northern Ireland counterparts to boost the digital strength of its citizens and businesses. Northern Ireland Cyber Security Centre works in tandem with the NCSC to ensure that the public, businesses, and charities all have access to the right advice, guidance, and support. The new Centre provides a centralised communications role for cyber security in Northern Ireland and will help deliver the Cyber Security: A Strategic Framework for Action – which closely aligns with the UK Cyber Security Strategy.

HUMAN INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTER-INSURGENCY

When the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre fell on the 11th September as part of the concerted Al Quaeda attacks on the USA who would have imagined that an industry rooted in Northern Ireland would take shape?

Furious at this cowardly attack by terrorists, the US resolved to strike out at the source of their pain. Reacting with fury, understandably, they arguably fell into the classic terrorist trap; they reacted from the heart rather than from the head – they sought revenge over justice. Rather than treating ‘Ground Zero’ as a huge crime scene, the US resolved to go to war. But with whom? The danger with waging war on a noun is that nouns are hard to beat. Like a war on drugs or a war on waste, the war on terror found getting to grips with the enemy difficult and often the collateral damage to civilians or the innocent proved both counter-productive and difficult at once. A break-through of sorts came in around 2006 when the US was heavily invested in both Iraq and Afghanistan with her loyal allies increasingly out of their depth as a more conventional fight increasingly became a fierce underground insurgency.

The UK was not in any better shape. Whilst it was firmly believed by most of the coalition nations – the UK in particular – that the British Army were the low intensity conflict experts, in fact the opposite was true as it turned out. The speed with which the Army had abandoned the expertise it had acquired of more than 30 years of low intensity operations in Northern Ireland was dismaying. The lesson learned against vicious sectarian groups, some of whom, like the Provisional IRA, had both an international dimension and huge wealth, had set it apart. But the British Army had failed to chart and teach what it had learned. Turning her back on the 30 years of violent experience, by the time it was heavily involved in the Post 9/11 wars the lessons were largely forgotten.

One incident clearly illustrates this. A UK Major General, in his virtually besieged HQ in Basra Province, lectured a visiting senior UK policeman on the lessons learned in Northern Ireland and how they were being used to teach the US how to do it. The policeman quietly enquired how many times the general had served in Northern Ireland. The general admitted he hadn’t actually served there. But Sir Ronnie Flannigan, former Chief Constable of the RUC and former Head of RUC Special Branch (RUC SB) had already worked that one out. The US sought British advice and ‘know how’. But as one US general told me ‘they talked in riddles and frankly without substance. We figured early on they, in fact, had little real idea, just a bunch of catchphrases.

By 2006 the United States Marine Corps’ Intelligence Activity (MCIA) sought to see through these catchphrases and riddles and carried out their own academic research. They had identified the utility of police special branch organisations in previous successful counter insurgencies, from Israel to Malaysia and including Northern Ireland. Tasked with recruiting and running informants and agents within subversive organisations the lesson had been well learned that, in order to defeat an insurgency, you must challenge their strategic narrative, dismantle them by penetration and above all act within the rule of law.

By April 2007 doctrine was being written for a US owned Police Professional Intelligence Programme or ‘PIP’ for the police services of client nations – primarily Iraq to begin with – in Northern Ireland, by retired RUC officers. Serving RUC Special Branch detectives visited the US and Iraq. The US came to Northern Ireland. In early 2008 a team of eight retired RUC SB officers deployed to Anbar Province, Iraq. From an initial strength of 4 Iraqi officers, by 2009 the Iraqi Police Special Branch was operating across Iraq with over 400 officers and running an impressive network of agents and informers. In 2010 the programme, now called the ‘Legacy’ programme and owned at the highest level in the US led Coalition in Afghanistan was being deployed across Afghanistan. With the addition of military agent handlers and a sophisticated surveillance and threat finance capability (penetrating the financial activity of the criminal groups) the Legacy programme was changing the nature of the struggle significantly. Most importantly the purpose had changed from a war to an enterprise against a criminal network.

The aim was no longer to inflict casualties on the other side but to arrest and gain convictions against the various self-styled groups. The vast majority of the expertise that was sought for this new approach to international subversion came from Northern Ireland and also from the Garda Siochana Special Branch. An understated industry (for obvious reasons) originating in Northern Ireland is delivering expertise and knowledge across the globe in subjects from public order to forensics and consensual policing.

All the while, the wars of the 21st Century raged and soldiers from Northern Ireland could be found on the battlefield. As a major recruiting source for the UK Armed Forces, the quality of recruits in terms of education alone, make them much sought after. Local regiments struggle to get their quotas locally as so many are harvested off at recruiting offices for the Army Air Corps, Engineers, Signals and Intelligence Corps (an excellent reflection on Northern Ireland’s education system).

Over several tours of duty, the Irish Regiments, 1st Battalion The Royal Irish Regiment (R Irish) and her 2nd (Reserve) Battalion and the Irish Guards as well as many individuals, serving with other regiments, arms and corps have brought distinction, pride and honour to the province far in excess of it size. Amongst the gallantry awards are several Conspicuous Gallantry Crosses (CGC) as well as Military Crosses (MC). Sadly, a number of Northern Irish have fallen in service in these theatres. Corporal Bryan Budd, born in Belfast but serving with the 3rd Battalion The Parachute Regiment, won the Victoria Cross for valour on 20th August 2006 in Sangin District, Helmand Province, Afghanistan but at the cost of his life. One of the Legacy Programme police mentors, retried D/Sergeant Ken Mc Gonigle, late RUC SB, was awarded a posthumous Queen’s Gallantry Medal (QGM) and the US Defence of Freedom Medal (having been nominated for the US Silver Star) for saving a US VS 22 Osprey helicopter with 16 on board, including a US Navy Vice Admiral and head of the Navy Seals. In doing so he gave his life to save others. When the new regiment of the UK Special Forces (UKSF) was founded, The Surveillance and Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR), both the first commanding officer and first Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) were from County Down and County Londonderry respectively. Sadly, the highly decorated RSM, David Patton, was subsequently killed in action, once more in Sangin, serving as a captain in the SRR in June 2006. Stood in the Pantheon of fame of military heroes who served with Northern Irish units but were not born in the province, must be Sergeant Talaiasi Labalaba of the SAS who was killed in action in The Battle of Mirabat. He came from Fiji to join the Ulster Rifles, there is still strong feeling within the SAS for this man to be awarded the VC he so richly deserves as it is with Lt Col RB Mayne DSO (3 Bars), Legion of Honour and Croix de Guerre.

CONCLUSIONS

Since 2016, Northern Ireland has the UK’s only land frontier with The European Union. The Windsor Framework still has to render this new economic border viable. These modern political issues should not blanket past achievements. It is a remarkable fact the only place in the world that took a meaningful part in the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, but that did not have its own source of coal was Northern Ireland. The industry that flourished and attracted so many to settle there for jobs and security saw the birth of an industrial powerhouse by the beginning of the 20th Century.

Much of that industry has now gone or has transformed to an almost unrecognisable extent. Yet, from the earliest days, it has been the human capital of Northern Ireland that has been our most valuable asset, be it as workers in industry, ingenious designers or servicemen and women, on land and sea and in the air. Some went onto the highest ranks. Some served in high profile theatres across the globe as well as those that served out of sight – beneath the Arctic Ice Cap in nuclear submarines, waiting, ready, should the unthinkable happen. Who knows what the future may hold? But what we can be sure of is that Northern Ireland will continue to be a rich vein of talent and innovation that will leave its mark on the defence of United Kingdom and indeed, the world.

Colonel Tim Collins OBE, retired British Army officer and Ulster Unionist candidate for North Down.

- Field Marshals Montgomery (Moville, Co Donegal) Alanbrooke (Colehill, Co Fermanagh) Alexander (Caledon, Co Tyrone) Dill (Lurgan, Co Armagh) Aukinleck (Enniskillen, Co Fermanagh) and Templar (Co Armagh) all had Ulster roots.

- ‘Young men all around us were being sucked into the peacetime Army, in the absence of other employment. It was the Royal Ulster Rifles that took delivery of our fellows in the main. After an absence of three months or so they would come back, stiff necked, head back automatons, on embarkation leave for India or Palestine. The tour of duty was seven years. Nobody in the district thought anything of young lad gong away from his parents and family for seven years. That was the Army and there was nothing more to be said.’ McAughtry’s War by Sam Mc Aughtry, Blackstaff press 1985, P 2.

- This was an agreed payment of £3.13 million per year to repay a government loan that had facilitated land purchase in Ireland.

- https://www.qub.ac.uk/sites/irishhistorylive/IrishHistoryResources/Shortarticlesandencyclopaediaentries/Encyclopaedia /LengthyEntries/NorthernIrelandandWorldWarII/

- Barton, Northern Ireland in the Second World War, pp 80.

- An estimated 720 died in a single night’s raid on Liverpool just over two weeks later. London lost 1436 lives on the night 10/11 May 1941. –(Richard Collier – The City That Would’nt Die (Corgi)London 1958 p 260.

- ‘I turned over one poor chap on a rocky, bloody crag on Tanngoucha. He was facing the right way, the last round of a clip in the breech and three dead Germans in front of him. His name was Duff. After it is all over – and the remainder of the Empire is understandably irritated with Ireland – I hope the countless Duffs, from both North and South and in all three services, will be remembered.’ Brigadier Nelson Russell, Commander 39 (Irish) Brigade, 1942-44.

- R. Doherty, In the Ranks of Death: the Irish in the Second World War, Pen & Sword, 2010, p. 26-30; Y. McEwen, “Deaths in the Irish Regiments 1939-1945 and the extent of Irish volunteering for the British Army”, Irish Sword, vol. 24, 2004-5, p. 81-98; B. Girvin, The Emergency, London, Pan Books, 2007, p. 274-5.

- National Archives of Ireland [NAI], Department of the Taoiseach [DT], S6091A, memorandum by Minister for Defence, “Assistance being afforded to Irish citizens to enlist in the British Army,” 6 May 1941.

- Born in Lurgan Co Armagh, his father was the manager of the Ulster Bank in the town. When he died in Washington in November, he was given a public funeral and interred in Arlington National Cemetery, the only foreign soldier buried there and the equestrian statue above his grave is only one of two in the whole cemetery, such was his standing in the USA.

- Citation for the US Distinguished Service Medal.

- Incidentally, the very same village from which President Andrew Jackson’s family had left in order to travel to the USA.

- A stick was a parachuting term for a group of SAS soldiers. Today, we call it a ‘Troop”.

- https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/opinion/news-analysis/how-northern-ireland-hosted-nazi-u-boat-fleets-defeat-31213440.html.

- After the war homeless families flooded in to squat in the camp. Eventually Derry city council accepted the state of affairs and issued rent books. The last residents left in 1967.

- https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/opinion/news-analysis/how-northern-ireland-hosted-nazi-u-boat-fleets-defeat-31213440.html.

- The Donegal Corridor was a narrow strip of Irish airspace that linked Lough Erne to the Atlantic Ocean and through which the Irish Government permitted flights by British and Allied military aircraft during WWII. This was of course, a contravention of Irish neutrality and so was not publicised at the time.

- Orr, David. A New Battlefield . Helion and Company. Kindle Edition.

- A story told at the time relates how prisoners, amongst them many of the Royal Ulster Riflemen, were subjected to a political lecture in a cave by a Chinese Political Commissar. The theme was ‘why are you fighting America’s war?’. At the end of the lecture an Ulster Rifles captain described the scene as ‘all were very depressed and down. We were hungry and cold and now told we were fighting a war that was not our business. Then the Commissar invited questions from the demoralised audience. There was some murmuring but mostly silence. Then, the skinny arm of a Rifleman at the back shot up. The Commissar invited him to stand up and shout out his question clearly so that everyone could hear. The Rifleman said ‘well, me and some of the boys – having heard your speech’… the commissar was nodding and smiling… he went on ‘were wondering, why you don’t go and F*** yerself?’. The cave broke into cheers, men shaking hands and shouts of ‘up the Rifles’ and ‘Happy New Year, ya Communist B******s’.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Salmon, Andrew. To The Last Round: The Epic British Stand on the Imjin River, Korea 1951. Aurum Press.

- Commander of the 29th Brigade.

- Ibid

- The Canberra was to see service during the Falklands War in 1982.

- Their network of allies, from the bloodthirsty ETA in Spain to the Narcotics giants of Colombia’s Fuersas Armas Revolutionary de Colombia (FARC) to Islamic terrorists and its enormous wealth.

- Sinn Fein, its political wing reportedly the wealthiest party in Ireland,https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/sinn-féin-is-the-richest-political-party-in-ireland-1.4193124.

- Author, Camp Blue Diamond, Ramadi, Anbar Province, Iraq, April 2007.

- An informer is an individual who passes information to his handler, sometimes casual back-ground information sometimes specific information, often without knowing the reason the information is needed. An agent is a knowing and willing member of a subversive organization. Sometimes at the highest level. It is now known, for instance, that as many as one in three of the Provisional IRA members were either agents or informants. Within so called Loyalist organizations the figure was even higher.

- Ken McGonigle had by the timer of his death retired from the RUC. The Silver Star cannot go to a civilian.

- Lt Col Blair Mayne died in a car accident in 1955 and is buried at the family plot in Newtownards.